WHAT EVERY NURSE SHOULD READ BEFORE EMBARKING ON A GLOBAL HEALTH CLERKSHIP

image by THE WING

Nothing could have prepared me for the magnitude of suffering endured by women with childbirth-related pelvic floor injuries I saw at obstetric fistula clinics in Niger and Rwanda. Late one afternoon, at a facility in Niamey, the capital of Niger, a young woman was assisted onto an examination table newly covered with a fresh stretch of rolled paper. She had taken each step towards the examination table with great difficulty. Her body moved sinuously with agony and her face furrowed into a grimace. She clutched the nursing assistants holding onto each of her arms as she walked. When she lay in a lateral position for the intake interview, tiny beads of sweat glistened on the bridge of her nose. My colleagues and I learned through an interpreter that the young woman had an at-home spontaneous vaginal delivery three days prior to our encounter. After each leg was carefully placed in stirrups, we discovered the source of her distress: an un-repaired third degree perineal laceration in the early stages of healing complicated by a small vesico-vaginal fistula.

THERE ARE NO HUMANITARIAN SOLUTIONS TO HUMANITARIAN PROBLEMS

SADAKO OGATA, former United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 1991-2000

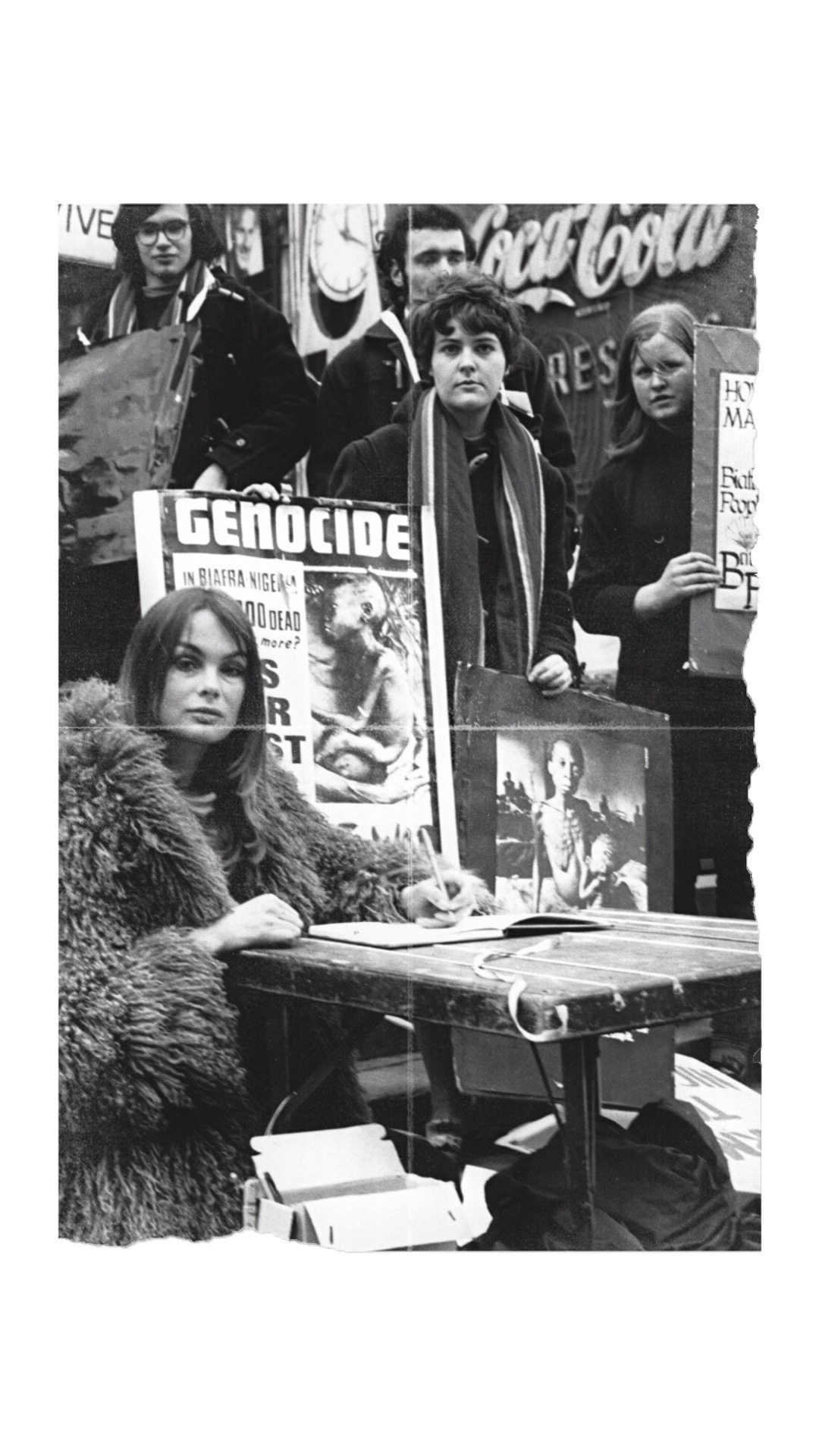

NewYorker staff writer Philip Gourevitch wrote in Alms Dealers that origins of the humanitarian aid model followed by wealthy nations today can be traced to the global response to shocking images of malnourished children that were broadcast around the world during the Biafran War of 1968. With no shortage of famine, disease and armed conflict in the ensuing decades to produce a steady supply of horrific images depicting maimed bodies and starving children, development assistance aid from the wealthiest to the poorest nations has increased 40-fold. According to the World Bank, net development assistance aid, which totaled US$4.3 billion in 1960, reached a peak of US$163 billion in 2017. Florence Nightingale, Gourevitch reports, was unequivocally opposed to humanitarianism because it absolved political leaders from bearing consequences of policies that induced or aggravated the same humanitarian problems targeted by aid agencies.

According to the Consortium of Universities for Global Health, almost 300 universities and colleges around the world offer international research and clinical clerkships designed to introduce students to global health problems. Increasingly, nursing schools across the United States are sending their students on such rotations in south America and as far away as sub-Saharan Africa. These immersions into foreign health systems confer clear benefits to students from high-income countries who gain exposure to novel (to them) pathologies and experiences. But, their effect on the ecosystems in which they are placed is not benign. Emphasis on familiarity with physiologic etiologies of clinical conditions should be matched with prioritizing comprehension of historical contexts of their host countries as well as the geopolitical and socioeconomic drivers of the diseases they encounter.

We have put together a selected bibliography consisting of contemporary literature addressing the triumphs and tragedies of humanitarian aid to further understanding about an unyielding paradox: how vast expenditure on development assistance has failed to overcome complex interlocking factors working in tandem in a precise proportion and sequence necessary to inflict debilitating clinical conditions like the one we saw in the young woman at the obstetric fistula clinic that afternoon.

Dead Aid: Why Aid is Not Working and How There is a Better Way for Africa

by Dambisa Moyo